by Yuliya Kazanova

This blog post focuses on one of the most underestimated novels in contemporary Ukrainian literature of recent years – The Road to Asmara by Serhiy Synhayivsky, which Vitaly Chernetsky discussed in his talk for the Harvard Ukrainian Summer Institute on 9 July 2021. I will summarize the key points of Chernetsky’s postcolonial critique and complement it with my reader’s review and interpretation of this text as a historical novel of Zabuzhkian type.

This blog post focuses on one of the most underestimated novels in contemporary Ukrainian literature of recent years – The Road to Asmara by Serhiy Synhayivsky, which Vitaly Chernetsky discussed in his talk for the Harvard Ukrainian Summer Institute on 9 July 2021. I will summarize the key points of Chernetsky’s postcolonial critique and complement it with my reader’s review and interpretation of this text as a historical novel of Zabuzhkian type.

Anticolonial solidarity in The Road to Asmara

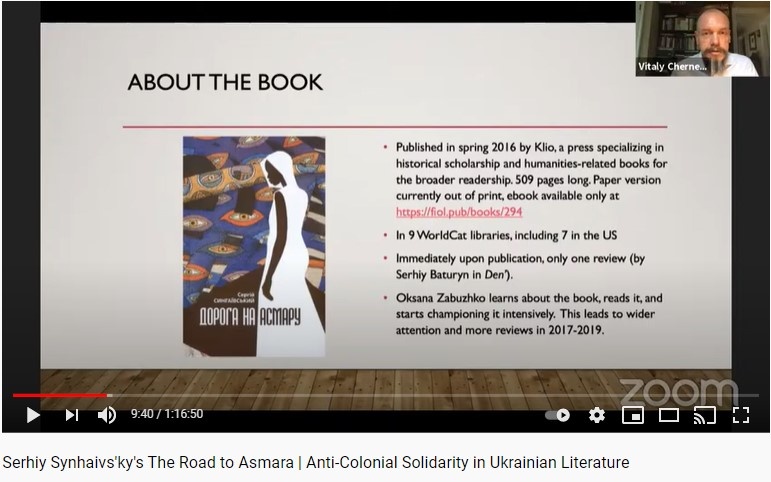

Published in 2016, Synhayivsky’s book went almost unnoticed by literary reviewers for a year until, by happenstance, it was read by Oksana Zabuzhko. One of Ukraine’s leading intellectuals, Zabuzhko has enthusiastically endorsed the novel and brought Synhaivsky, whom she dubbed ‘a Ukrainian Graham Greene,’ into the spotlight by inviting him to a series of discussions, which she hosted at 2017 Book Arsenal Festival. This publicity placed the novel on the literary radar for readers and scholars. However, speaking four years later, Chernetsky remarked that in in 2021 this work still lacked the recognition that it richly deserved as ‘a beautifully written, absorbing work of fiction with a captivating semi-detective plot.’

Although the book is his debut as an author, Synhayivsky is an established literary translator who served as a military interpreter in Ethiopia in 1984–1987. The novel is based on his first-hand experience of the Ethiopian famine of 1983-85, which claimed the lives of approximately one million people and was deliberately used by the government to suppress the pro-independence insurgency in the northern provinces of Tigray and Eritrea. In his novel, Synhayivsky draws insightful parallels between the Ethiopian disaster and the Holodomor, as well as between Soviet racism in Africa and Soviet cultural policy in Soviet Ukraine.

Chernetsky contextualised The Road to Asmara within the paradigm of postcolonial writing, both in Ukrainian and world literatures. This text, he argued, made ‘an essential new contribution to the Ukrainian literary tradition of anti-colonial solidarity,’ which goes back to Taras Shevchenko’s poem ‘Kavkaz’ and still has a strong presence in contemporary writing, as evidenced by the solidarity with Jewish suffering in the poetry of Marianna Kiianovska and Aleksandr Overbuch. In a wider literary context, Chernetsky identified Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness as an important intertext for Synhayivsky’s novel and singled out the identity quest of Synhayivsky’s protagonist as a typical plot in postcolonial works of world literatures.

Concurring with Zabuzhko, Chernetsky remarked on Synhayivsky’s original contribution to Ukrainian literature with his Andriy Volynsky, a brand-new type of protagonist drawn from the tradition of international postcolonial fiction. Throughout the novel, Andriy’s journey of awareness takes him outside his whiteness and Soviet racism toward deep solidarity with the Ethiopians and a new understanding of his own national identity. Chernetsky also remarked on Synhayivsky’s ‘respectful engagement with multicultural and multilingual situation in Eritrea.’ He argued that this sensitive treatment of the difficult colonial past makes the novel valuable for both Ukrainian and global audiences. Specifically, this text may help Ukrainians actively confront Soviet imperial legacies and undertake the work of mourning for colonial traumas. Meanwhile, the readers outside Ukraine would be interested in Synhayivsky’s depiction of the horizontal networks of solidarity, developed by nations of Eastern Europe within complex global networks.

At the moment, The Road to Asmara is out of print and only available as an e-book, with provisional plans for an English translation. The second edition of this novel in Ukrainian and an English translation hopefully would give this underestimated novel a wider readership, which it definitely merits.

The Road to Asmara: A reader’s review

I happened to be one of those who bought Synhayivsky’s novel, then still available in bookshops, on the wave of enthusiasm raised by Oksana Zabuzhko. The heavy 500-page volume had been standing idle on my bookshelf for several years until I finally read (or rather, devoured) it on the eve of Prof. Chernetsky’s talk. I was immediately gripped by the quest plot, which follows Mykyta Nefiodov, a contemporary Ukrainian architect, as he discovers the turbulent past of his parents, Ukrainian painter Iryna Sulyma and Russian KGB colonel Eldar Nefiodov, as well as Iryna’s lover and Mykyta’s biological father Andriy Volynsky.

The vivid narrative of the novel offers an immersive experience, especially in the Ethiopian travelogue chapters, which mingle Andriy’s terse diary entries with episodes narrated from an omniscient author’s perspective. In the laconic style reminiscent of Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter, Synhayivsky captured the riveting strangeness and beauty of African landscapes and people, which eludes the glance of Europeans, blind-folded by racial stereotypes and engrossed in the petty squabbles of their daily life in a foreign land.

None the less graphic is the recreation of the claustrophobic atmosphere of the Soviet late stagnation period, reflected in the microcosm of Soviet military community abroad. This world is shaped by the ever-present and ever-listening KGB osobisty who snub meaningful conversations, the traumatized veterans of the ongoing Afghanistan war, the heavily drinking soldiers, the despairing young families who face decade-long lists for state housing and prohibitively expensive private kooperatyvy. As Andriy Volynsky tells the diasporic Ukrainian Raya Kleparchuk, he volunteered for the military posting that landed him in Ethiopia because this was his only chance to earn enough money to buy their own flat in a kooperatyv. This admission makes Andriy realize the unfreedom of his life in the Soviet Union, which made him into a mercenary profiteering on a humanitarian catastrophe: ‘Андрій відчув, як червоніє від раптової люті на себе, на абсурдність свого становища, що її так легко вгледіла ця представниця вільного світу, яка прибула сюди за покликом душі’ (p. 215).

I also appreciated the dense literary texture of the novel, which abounds in characters who read and refer to classical works of European and Russian literature that were available in the Soviet Union: among others, Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas, William Styron and Ernest Hemingway, the Strugatsky brothers and Stanislav Lem, Alexander Pushkin and Lev Gumilyov. However, some characters and plot twists left me with a lingering sense of déjà vu. For instance, an intense love affair in an exotic African wartime setting, with a jealous husband who (nearly) kills the lover in an air crash, strongly evokes the central plot of Michael Ondaatje’s novel The English Patient.

Most visibly, The Road to Asmara is modeled on the type of multi-generational historical novel, represented by Zabuzhko’s The Museum of Abandoned Secrets. Both texts highlight the moments of paradigmatic political shifts: the Revolution on Granite of 1990 and the Orange Revolution of 2004 in Zabuzhko, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Revolution of Dignity of 2014 in Synhayivsky. Zabuzhko’s novel draws parallels between the oppressive atmosphere of Brezhnev’s stagnation era of the 1960-80s and President Kuchma’s two terms (1994-2005), terminated by the revolutions. In a similar vein, Synhayivsky links the tumultuous times of perestroika in Soviet Ukraine of late 1980s and the murky period of President Yanukovych’s term (2010-2014). The present and the past plots of both novels are connected via the melodramatic motif of an orphaned child searching for a true father. Both texts feature an antagonist, an MGB/KGB officer who kills the protagonist and, being infertile, adopts and brings up his enemy’s son (Captain Bukhalov and Adrian Ortynsky in Zabuzhko; Nefiodov and Volynsky in Synhayivsky). Like Zabuzhko, Synhayivsky concludes his novel with perpetuation of traumatic and repressed family memory via art (Daryna’s film and Mykyta’s musical). However, these affinities with Zabuzhko’s novel by no means demean the value and originality of Synhayivsky’s text, but rather signal his literary lineage and his desire to develop this model of a Ukrainian post-Soviet novel and thus explore the country’s difficult and unvoiced past.

This realistic and sensitive engagement with the Soviet past in the spirit of anticolonial solidarity, rich intertextuality, and deep embeddedness in the national and global literary context firmly puts Serhiy Synhayivsky’s The Road to Asmara on the map of contemporary Ukrainian literature. Its wider readerly and critical acclaim seems only a matter of time.

Further resources

Serhiy Synhayivsky, The Road to Asmara (Kyiv: Klio, 2016)

‘Rozkazhy meni pro mene. Den’ 4. Oksana Zabuzhko i Serhiy Synhayivsky.'