by Alisher Juzgenbayev, HUSI 2021

When I first read the description of Professor Dibrova’s Ukrainian for Reading Knowledge class, I knew how I would like to spend this summer. As a J.D./Ph.D. student interested in the relationship between law and politics in countries of the form Eastern Bloc, I was thrilled by the possibility of getting crucial language skills and by the prospect of learning from a diverse group of scholars who are passionate about the region. For someone who spends a lot of time reading court orders, legal documents, and foundational political acts, there seemed to be no better way to apply my newly gained knowledge of Ukrainian than to attempt to read one of the most important documents in Ukrainian History – the Pylyp Orlyk Constitution.

When I first read the description of Professor Dibrova’s Ukrainian for Reading Knowledge class, I knew how I would like to spend this summer. As a J.D./Ph.D. student interested in the relationship between law and politics in countries of the form Eastern Bloc, I was thrilled by the possibility of getting crucial language skills and by the prospect of learning from a diverse group of scholars who are passionate about the region. For someone who spends a lot of time reading court orders, legal documents, and foundational political acts, there seemed to be no better way to apply my newly gained knowledge of Ukrainian than to attempt to read one of the most important documents in Ukrainian History – the Pylyp Orlyk Constitution.

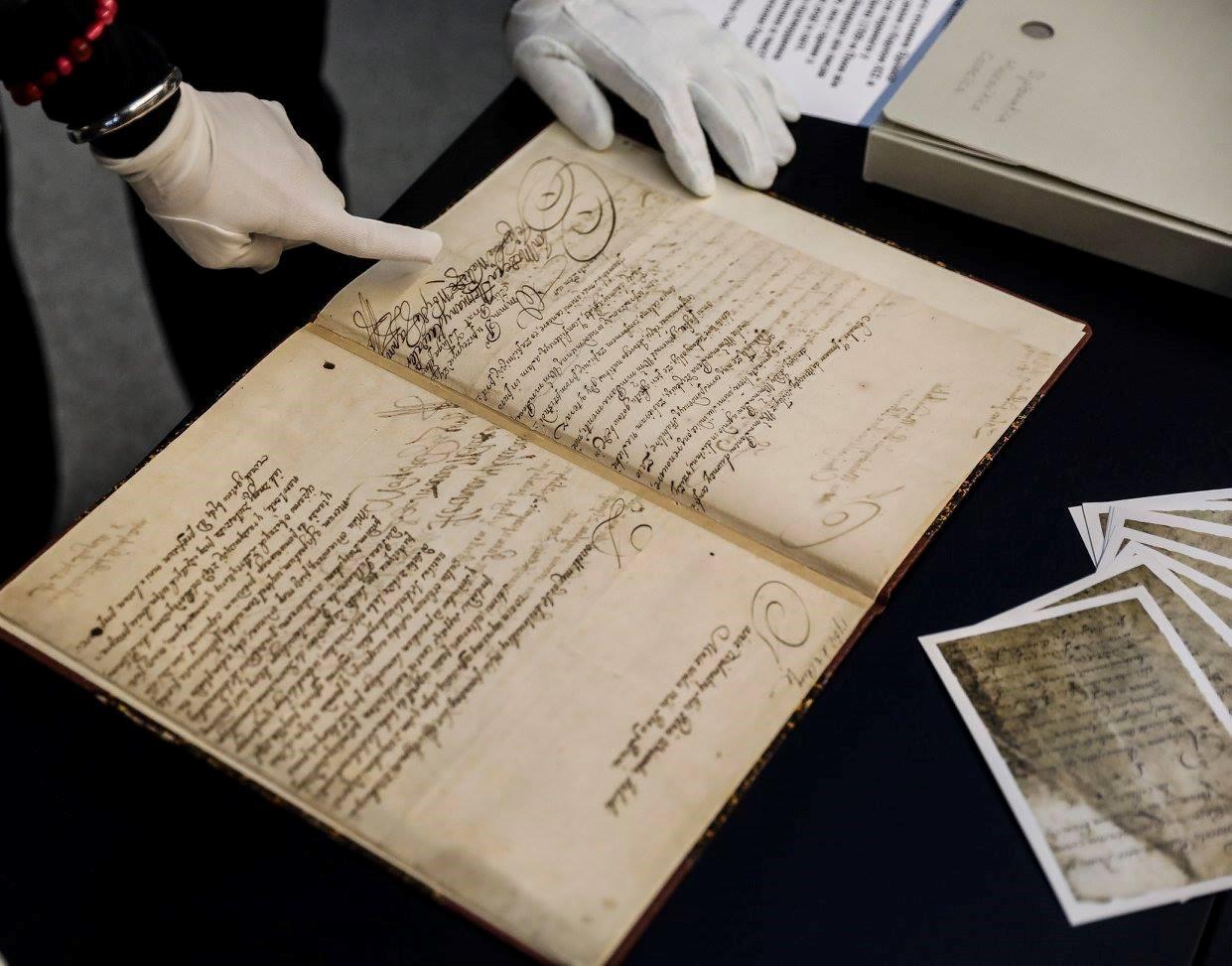

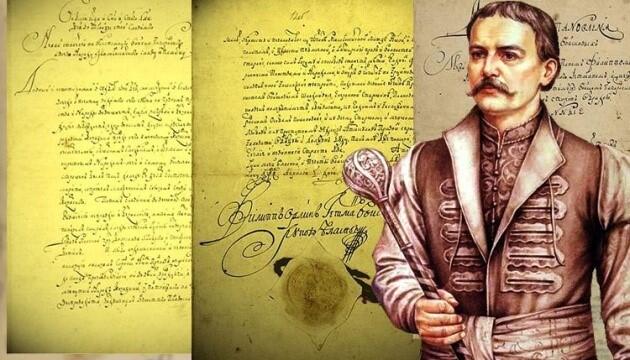

Published in 1710 by then in-exile Hetman of Ukraine Pylyp Orlyk, this document represents the height of Ukrainian legal-political thought in the early 18th century. Constitutions provide information regarding how the people of the past wished to organize their society and distribute political power, but they also give rare glimpses of how those in power saw their society, and how they wished to be seen by their neighboring nations and empires. While there is considerable debate regarding the nature of this document (a considerable dispute is centered on seeing this act as an “agreement,” “constitutional act,” or a “constitution”),1 its value as an object of historical inquiry is unquestionable.

The lengthy preamble of the text traces the history of the Cossacks of the Zaporozhian Host to the Khazars, semi-nomadic people who lived, among other places, in the lands of contemporary Ukraine.2 It talks about the Christianization of the lands and ties with the Byzantines. Khmelnytskyi’s Uprising is then seen as a defining moment of liberation against Polish oppression, where seeds of Cossack statehood were sown, and which, to the dismay of writers of the text, tied its destiny to the Orthodox Muscovy State. The language of the preamble is, in some sense, similar to the subsequent US Declaration of Independence. Just like the Declaration, the Preamble to the Orlyk Constitution attributes its existence to injustice and violence (“насильство”), in this case of the Muscovy state amidst Hetman Mazepa’s attempts to regain the Cossack rights and freedoms (“права та вольності військові”). Thus, appealing to God, the document, with the consent of the Zaporizhian Army, Hetman, and the General Sergeant (“Генеральна Старшина”), aimed to set out the structure of the Cossack state.

Although several military victories in 1711-1713 enabled the application of the text to some parts of right-bank Ukraine, this document did not enter into full force in all the lands that are now part of Ukraine, which ultimately were incorporated in the Russian Governorate of Kyiv. Ukrainian historian Alphorov attributes the West’s lack of knowledge and recognition of the text as the first modern constitution that predated the publication of Montesquieu’s Spirit of Laws to this ultimate loss of autonomy by the Cossacks.3

The primary provisions of the Constitution themselves are worth delving into. The text specifically mentions fear of autocracy (“влада самодержавна”) as a motivating factor for the limitation of the Hetman’s powers. By design, the Hetman could not freely tap into the state treasury, pursue foreign policy, and set up personal administration without the consent of General Rada, a council comprising officers, city colonels, and councilors.4 Moreover, no punishment for offenses, criminal and civil, could be disposed of unilaterally by the Hetman. Such power was only given to the General Military Court. Omeljan Pritsak notes the influence of liberal ideas on the document: its nature as a social contract, focus on obligations and duties of the Hetman, and the foundation of state power being vested in elections.5

That the Constitution was the product of its time is evident, not only in certain early Enlightenment ideas, but also in the provisions limiting religious freedom, except for the Orthodox Christians, and specifically excluding Judaism from the public and private sphere, following the history of brutal violence against the Jews during Khmelnytskyi’s rule (Article I). Nor has the Constitution specified the right to vote in an explicit sense that is given to those who are not part of the military ruling class of the Hetmanate.

While recognizing its shortcomings and putting it in the historical context of absolutism in Europe, one can recognize the profound importance of the document, which reflects and prefigures contemporary debates in Ukraine surrounding religion, relationship with the West and Russia, abuse of the political office, and corruption. As Pritsak put it: “the formulation of the Constitution should be recognized as the early stage of the Ukrainian tradition of constitutionalism.”6 This tradition is alive today and undergoes profound changes, and I am fascinated to witness the direction which it takes.

1S Holovaty, “So What Actually Is Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk?,” Law of Ukraine: Legal Journal (Ukrainian) 1 (2016): 113–29.

2Omeljan Pritsak, “The First Constitution of Ukraine (5 April 1710),” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 22 (1998): 471–96.

3Українська правда, Перша Конституція України Та Яким Був Її Автор Пилип Орлик, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkK0b7vMIuI.

4Bertil Haggman, “The Bendery Constitution and Pylyp Orlyk and His Government-in-Exile in Sweden in 1715-1720,” Law of Ukraine: Legal Journal (Ukrainian) 1 (2020): 288–301.

5Pritsak, 119.

6Pritsak, 128.