Olga Khomenko is a Fulbright visiting scholar at HURI for the 2018-2019 academic year. Her research focuses on the intersection of Japan and Ukraine, particularly through the lives of the Ukrainian diaspora in the Far East. On Thursday, April 4, she will be HURI's Ukraine Study Group speaker and will present, "Making a 'Little Ukraine' in China: A Historical, Intellectual, and Social Portrait of the Diaspora (1897-1949)." The event will take place in the Omeljan Pritsak Memorial Library at HURI (34 Kirkland Street) at 12:15 p.m. and is open to the public.

An associate professor of history at The National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy in Ukraine, Khomenko has been studying Japan for the last twenty years.

Her entry into the field was inspired by Japanese artwork, such as woodblock print and Sumi-e, which she encountered at art school as a child. Throughout her academic career, her interests have spanned several topics, from literature to business.

"My senior thesis examined the history of the Japanese translation of works by Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko," she said. "Subsequently, I studied the Meiji Restoration and modern state development in Japan during my MA studies at the University of Tokyo. Later, during my doctoral program, I researched the postwar development of Japanese society, in particular its business and media history. Since 1994, I have been a member of the Japanese Society of Ukrainian Studies. During the 1990s, I also worked as a cultural attaché for the Ukrainian Embassy in Tokyo."

More recently, Khomenko translated Ukrainian fairy tales into Japanese and published a Japanese-language book of essays on Ukrainian culture and history. The collection, From Ukraine with Love, includes personal stories about eighteen people who faced historical changes - such as the Chernobyl nuclear disaster - and two essays outlining what architectural landmarks in Kyiv reveal about Ukraine's past.

Khomenko recently answered some questions to give us more insight into her research and the upcoming talk.

What is your current research project?

I came to HURI as a Fulbright visiting scholar, and my research will seek to draw a wider historical picture of the Ukrainian presence in the Far East. I also focus on the historical, social, and cultural history of the Ukrainian diaspora in the Far East and its process of identity creation over an expansive territory and at the confluence of the geopolitical interests of three world powers, namely Russia, Japan and China. As a professionally trained historian of Japan, I am interested in Ukraine-Japan contacts and relations, as well as cultural and historical encounters between the two countries.

Diplomatic relations between Ukraine and Japan were officially established only recently, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Two years later, a Japanese embassy was opened in Kyiv. However, cultural contact between Ukrainian and Japanese people took place earlier, in the second half of the nineteenth century, when, after the Meiji Restoration, Ukrainians started to visit Japan with specific diplomatic and cultural missions. The very first Russian consul to Japan, Iakov Goshkevich, had Ukrainian roots, while the blind poet Vasyl Yaroshenko was the first Ukrainian to write in the Japanese language and to be published in Japan. European anarchist Leo Mechnikov, who introduced anarchism to Japan, was the brother of the academic Ilya Mechnikov, a famous medical doctor who lived in Ukraine and was expelled from the University of Kharkiv for participating in the radical student movement of 1856. Ukrainian actor Petro Karmeliuk-Kaminski and his theater entertained Japanese audiences in Tokyo and Kobe in 1916. Then, the first Japanese diplomatic-consular mission to Ukraine was established in Kyiv during the country’s brief period of independence in the revolutionary years of 1917-1918.

Ukrainian-Japanese relations have not always been easy. On the one hand, Ukrainians participated in the Russo-Japanese War as well as World War II on the side of Russia and then the Soviet Union. In fact, the act of Japanese surrender was signed by the ethnic Ukrainian Kuzma Derevyanko, who represented the Soviet side. On the other hand, when Ukrainians were trying to establish their own permanent independence after the failed attempts of 1917-1918, they cooperated with the Japanese in an effort to set up a Ukrainian autonomous political enclave in the Far East called Zeleniy Klyn (the “Green Zone”), or Zakytaischina, literally meaning “the land over China,” in the interwar period. The territory concerned encompassed one million square kilometers near the Amur River and Ussuriyskiy region and later became incorporated into the wider territory stretching from Lake Baikal to the Bering Strait.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the Russian Far East became an attractive destination for Ukrainians mainly hailing from the central part of Ukraine, namely the regions of Chernihiv, Poltava, Sumy and Kharkiv. In the Far East, these Ukrainians hoped to find free land and start a new life. Over 1.5 million people lived there and about one million of them were Ukrainian. Also, the Far East had always been a sphere of interest of neighboring countries, such as China and Japan, and they were aware of the significant concentrations of Ukrainians living in the area. For example, Japanese embassies in Germany and China between the World Wars had a specially appointed officer who handled relations with Ukrainian emigre communities in Germany and China, mostly because the Japanese government was thinking about supporting the creation of an independent Ukrainian enclave in the Far East.

I am now doing research on the Ukrainian diaspora in the Far East, especially in China from 1922 to 1947. During these years, many prominent Ukrainian intellectuals were fleeing Bolshevik communism for Harbin, China, after the Soviet state took control over the Russian Far East. Through the figure of Ivan Svit, a journalist, historian, and the first scholar of Japanese studies in the history of Ukraine who wrote a book titled History of Ukrainian-Japanese Relations, I am trying to draw a bigger picture of the Ukrainian diaspora in China, especially during the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. I also reconstruct Svit’s personal and political networks by examining the people who had contact with him during his time in the Far East.

Who is the main figure of your research?

Who is the main figure of your research?

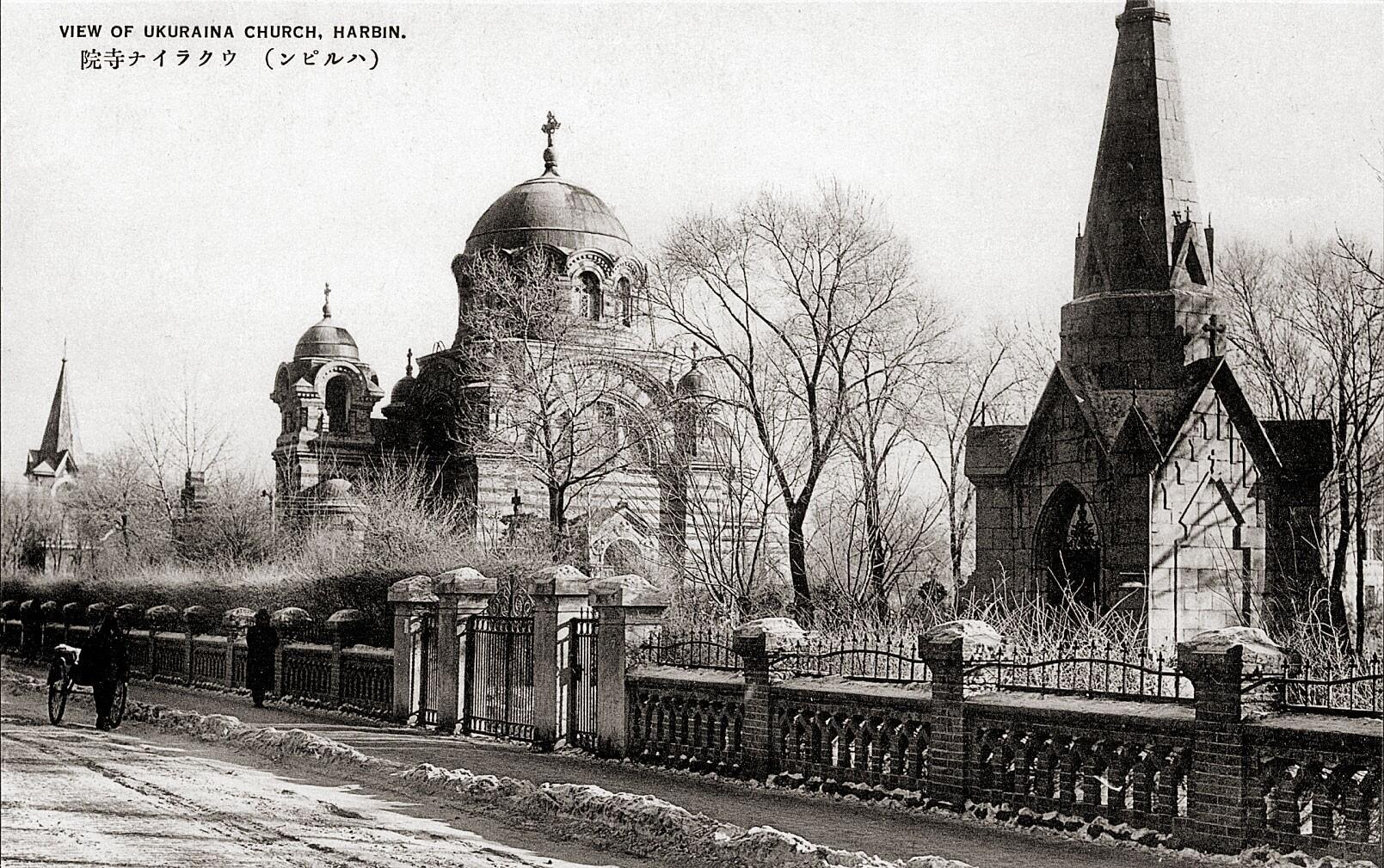

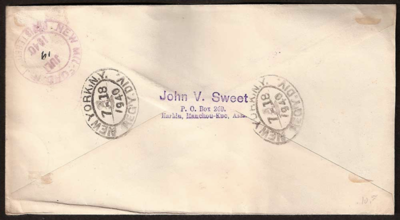

I am interested in a person named Ivan Svit, or John V. Sweet, as he was known in the United States. Svit was born on 27 April 1897 in Kharkiv region and became the main figure of the Ukrainian emigrant community in China. His original name, prior to his conscious embrace of his Ukrainian identity, was Ivan Svitlanov. He was a Ukrainian historian, journalist, and social activist in the Far East. He had been educated at a seminary and then studied mathematics and physics at Kharkiv University. In March 1918, he moved to the Far East, originally intending to move to the United States. However, he ended up living between Vladivostok, Japan, and China from 1918 to 1949. Svit published a Ukrainian periodical in Vladivostok and, in October of 1922, immigrated to Chinese Harbin, where he worked at a newspaper. He was a key figure within the Ukrainian expatriate community. When Manchuria was taken over by the Japanese in 1932 and Manchukuo was established, there were 11,000 Ukrainians living in Harbin, where a Ukrainian National House had been established. Ivan Svit was one of the founders and writers of the Ukrainian weekly paper in Harbin called the Manchurian Bulletin ( 1932-1938) which appealed to the substantial Ukrainian emigre population in Harbin. That publication lasted through the Japanese occupation.

In China, Ivan Svit ran a small stamp business, which, compared to other people, gave him a stable income and helped him to survive this difficult time, during which he was very active in the Ukrainian community. In 1944, he participated in creation of the first Ukrainian-Japanese Dictionary. Later, with the collapse of Manchukuo and the arrival of the Soviet Army to China, he moved from Harbin to Shanghai, where he was a member of the Ukrainian National Committee of Shanghai. There, he helped produce documents to move about 200 Ukrainians out of China to the USA, Argentina, and Australia. He was, in a way, a self-proclaimed consul and helped many people survive. I could even say that he was like the Japanese diplomat Sugihara, but for Ukrainians in China.

Ivan Svit himself moved to Taiwan in 1949 and then, in 1951, he continued on to Alaska and then to New York. He became a member of UWAN (Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Science) and researched the history of the Ukrainian emigre community. In 1972, he published a book on the history of Ukrainian-Japanese relations, which still today remains the only existing proper book on the topic. Svit was interested in many topics: he wrote about economic affairs, Ukrainians in Asia, Ukrainian activities in the Far East, and many other things. He was also a sucessful entrepreneur. He was never known during Soviet rule in Ukraine and largely has been ignored by Ukrainian historians to this day, mainly because he represented Ukrainian emigre communities that left the Soviet Union for ideological reasons.

I am looking at Ivan Svit and his life from two perspectives. The first concerns his role as a pioneering figure in the history of Ukraine-Japanese cultural relations. He was never trained as a professional Japanologist, but by the circumstances of his dramatic life, at the beginning of which he studied to be a priest and mathematician in Ukraine, he learned a lot about Japan and Asia and was able to write an entire book on these parts of the world.

The second viewpoint regards his activity in developing Ukrainian knowledge about Japan as well as spreading knowledge about Ukraine around the Pacific and Japan in the context of the interwar tensions, World War II, and the Cold War. It is important to have a look at how his view was changing during the fall of the Japanese Empire and the transformation of the global geopolitical situation, as well as to consider his related connections to the Ukrainian diaspora.

Ivan Svit was also a successful entrepreneur who owned postage stamp shops in Harbin and Shanghai. He juggled his historical interests with running a business and owning a shop, allowing him and his family to survive through difficult years in China. Svit has a very interesting personality and his story could serve as a great example for many Ukrainians who are now surviving exceptional and difficult times. His life could likewise be an excellent model for today’s young Ukrainians, who could learn from Svit’s case how to be successful in entrepreneurship and still have a stimulating intellectual life.

What is your bigger research picture?

What is your bigger research picture?

By analyzing neglected primary sources left behind by Ukrainians living in the Far East and piecing together their biographies, intellectual output, and legacies, my aim is to chart a wider history of the construction of Ukrainian identity outside of Ukraine during the turbulent twentieth century. By closely investigating who these people were, when and how they moved to the Far East, and what their educational backgrounds and religious beliefs were, I think that we can develop a better appreciation of the historical significance of the Ukrainian diaspora in the Far East and China. The story of Ivan Svit and his diverse cast of affiliates can also serve as an illustrative case study in the formation of transnational intellectual networks, the politics of national identity and self-fashioning, and the mobile lifeworlds of people caught at the confluence of empires. My hope is to draw on a rich base of sources and present an accessible narrative from which other researchers and the broader reading public can benefit.

What fascinates you about this topic?

I learned about Ivan Svit in the mid-90s from my professor, Kazuo Nakai, a prominent Japanese professor of Ukrainian studies. He had met Svit in the US in the early 80s. Professor Nakai gave me a copy of Svit's book. I was very fascinated by its contents and later used it in my classes.

I am totally impressed by the survival skills of Svit and the people in his network. Sometimes people say that Ukrainians, due to many traumatic experiences during the twentieth century, sometimes tend to engage in so-called “self victimization.” But this turns out to be not true at all, especially if you look at the trajectory of the life of Ivan Svit and other Ukrainians living in China. Their ability to adjust to different places, like Vladivostok, Harbin, Shanghai, Taipei, Alaska and New York are true examples of what business scholars call “adaptive leadership.” These people were not only adapting to new cultures and places, but were also very active in articulating their Ukrainianess socially and culturally. They also set a good example of public diplomacy through the service they did for Ukraine in the Far East.

◊

Dr. Olga Khomenko is a Fulbright visiting scholar at the Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University. She holds a PhD in Area Studies, specifically on the history of Japan, from the University of Tokyo (2005), a PhD in world history from the Ukrainian Academy of Science (2013), and an MBA from the Kyiv School of Economics (2017). She is an Associate Professor in the History Department of The National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy, Ukraine. Previously, she was a Japan Society for Promotion of Science visiting scholar and a Hakuho Foundation international fellow. Her research interests include the history of postwar Japan, the history of Japanese business and consumption culture, the history of Ukraine-Japan relations, with a focus on Ukrainians in the Far East and Manchuria under Japanese occupation, as well as the history of the creation of Ukrainian national identity and Ukrainian literature. Khomenko wrote a book of essays on the history of Ukraine titled, From Ukraine with Love (Gunzosha, 2014), and the co-translator of Modern Anthology of Ukrainian Literature (Gunzosha, 2005), both published in Japanese. She is also the author of numerous articles on the history of business and consumer culture in Japan.

Dr. Olga Khomenko is a Fulbright visiting scholar at the Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University. She holds a PhD in Area Studies, specifically on the history of Japan, from the University of Tokyo (2005), a PhD in world history from the Ukrainian Academy of Science (2013), and an MBA from the Kyiv School of Economics (2017). She is an Associate Professor in the History Department of The National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy, Ukraine. Previously, she was a Japan Society for Promotion of Science visiting scholar and a Hakuho Foundation international fellow. Her research interests include the history of postwar Japan, the history of Japanese business and consumption culture, the history of Ukraine-Japan relations, with a focus on Ukrainians in the Far East and Manchuria under Japanese occupation, as well as the history of the creation of Ukrainian national identity and Ukrainian literature. Khomenko wrote a book of essays on the history of Ukraine titled, From Ukraine with Love (Gunzosha, 2014), and the co-translator of Modern Anthology of Ukrainian Literature (Gunzosha, 2005), both published in Japanese. She is also the author of numerous articles on the history of business and consumer culture in Japan.